Inspired by the lack of cosmetic PFAS research in North America, in 2021 Whitehead et al. from the University of Notre Dame published a multi-year study wherein they examined the fluorine content, an indicator of PFAS, of 231 North American cosmetic products. Widely unregulated by policy, PFAS, a carcinogenic and ubiquitous chemical class used in a range of domestic products, do not require disclosure on product labels in the United States and Canada, despite their known toxicity. Whitehead found that of the foundations, eye products, mascaras, and lip products that were tested, nearly half to over half had high levels of fluorine present, measured at levels above 0.384 μg F/cm².

While these unregulated rates of dangerous “forever chemicals”, monikered as such for their inability to break down, are alarming from a general public standpoint, women, or more broadly those striving toward a more traditionally feminine appearance, face a greater risk of contact and consumption of PFAS due the reliance of femininity on cosmetic products. In order to uphold the feminine identity, accelerated in the 20th century by commercialization and cosmetic marketing, popular feminine culture tells us that we must make up our faces, buy the latest products, and, consequently, subject ourselves to the unregulated chemicals in these same products. The commercialized nature of makeup and femininity are captured under the term postfeminism, summarized in Jiyoung Chae’s analysis of post-feminine YouTube makeup tutorials (2021) as the proud and hypersexual way women reclaim womanhood through control of their appearance. In this reclamation, postfeminism is feminism, but in striving for control, women bury themselves deeper in a gender binary and contribute to capitalist consumption patterns.

To view this topic through an environmental sociology lens, ecofeminism and risk society provide frameworks that glean insight into the interplay between women as consumers of cosmetics and the PFAS market. Gould et al. (2021a) highlights the role of ecofeminism in sociology by exploring how environmental degradation is employed not only through capitalism, but by the patriarchy, as well. Justin Sean Myers, one of the contributors of Gould et al.’s Twenty Lessons in Environmental Sociology writes “these processes [womanhood and the environment] overlap in how capitalist patriarchy sees both nonhuman nature and women as property, commodifies both in the pursuit of profit, and exploits and appropriates the free labor of nonhuman nature and women” (p. 49). The cosmetic industry commodifies women’s bodies to chase profits, but this bottom line encourages a lack of regulation on ingredients, such as PFAS, that pose risks to these very same bodies. From the same chapter, Myers’ also discusses Ulrich Beck’s theory of risk society, stating “that high-income Western countries are no longer industrial societies but risk societies” (p. 46). In these “risk societies”, consumerism has shifted from concern about acquisition to concern about avoiding risk and distributing risk adequately. Given the consumer aspect of this essay, risk society theory speaks to the anxiety that cosmetic patrons face when trying to avoid chemicals like PFAS, especially when they are not required to be listed explicitly on ingredient labels. Feminine bodies, with their social upholding in makeup and consumerism, lie at this intersection of ecofeminism and risk society theories, and analyses of them in regards to the cosmetic industry must include both disciplines.

Causes

In the same study mentioned in the introduction, Whitehead et al. (2021) contextualize the use of PFAS in makeup for their hydrophobicity and ability to form films. And, indeed, the water-proof and long-lasting cosmetics they tested contained the highest amount of the PFAS indicator element. Once thought to be harmless, PFAS, short for poly- and perfluoroalkyl substances, emerged in the mid 20th century as a group of 5,000 similar chemicals used in products ranging from non-stick cookware to food wrappers to cosmetics. Besides directly exposing humans to these chemicals via household products, major PFAS producers like 3M and Dupont have been, knowingly, releasing PFAS into nearby soil and groundwater during production, contaminating massive amounts of water systems across the US (Gould et al., 2021b).

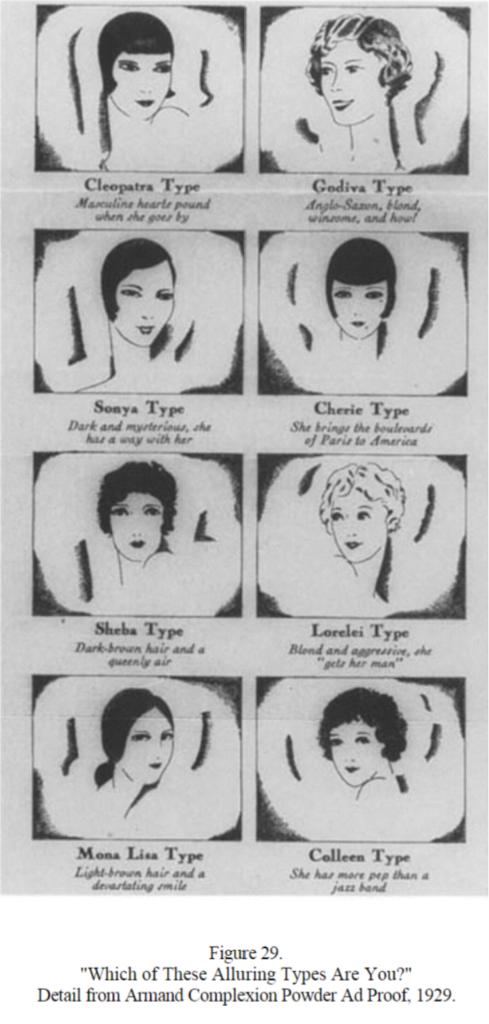

While millions of Americans are drinking PFAS contaminated water, cosmetic users are subjected to even higher levels of PFAS exposure. From the book The Sex of Things : Gender and Consumption in Historical Perspective (De Grazia & Furlough, 1996), Kathy Peiss writes in their chapter titled “Making Up, Making Over Cosmetics, Consumer Culture, and Women’s Identity” (pp. 311-331) about how, before the emergence of mass consumerism in the 1900s, a person’s identity was shaped more by their character, immutable traits, than their personality, adaptable traits. Personal traits could now be purchased; one could intentionally influence the way in which others saw them, and the cosmetic industry saw this as an opportunity to sell to women who wanted to achieve a certain perception. Certain made-up looks connoted certain types of women, represented in this 1929 advertisement (De Grazia & Furlough, 1996, p. 325):

Conforming to established appearances (poised, composed, made-up) helped women uphold specific notions of their personalities, allowing them to emerge in the public sphere in a way that still aligned with the male perception of what a woman should be. To maintain their public presence, women had to conform to these stringent, male-imposed identities and roles that still reinforced traditional womanhood: waitresses, secretaries, teachers, entertainers, etc. And, in shoehorning their way into the labor force, they also reinforced these “types” of women that held these roles, very much in an early postfeminism manner (De Grazia & Furlough, 1996, pp. 311-331). Wearing makeup and appearing a certain way became critical to a woman being able to exist in the public sphere, and so, the cosmetic industry flourished in supplying women with these “means” of their production. This historic relation between women’s beauty standards and the public sphere, while shaken by various feminist movements throughout the years, remains central to the perception of the professional, or beautiful, women today.

Consequences

With this cosmetic boom of the 20th century, ecofeminism and its relation to capital skyrockets, becoming wickedly entangled into the 21st century. The production of these makeup products do not come without harm to the natural world and, by extension, feminine bodies. An article from the American Cancer Society (Simon, 2019) covers a 2019 National Health Institute study that concluded with a definite association between increased breast cancer risk and use of permanent hair dye and chemical treatment. The 2021 Whitehead et al. study pursued their study of PFAS in cosmetics due to the known environmental and accumulating harm of the range of chemicals. The Agency of Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, a sub agency of the CDC, concedes more studies need to be conducted on PFAS, but does list the following risks of exposure: increased cholesterol, blood pressure, and pre-eclampsia in pregnant women; decreased vaccine response for children; decreased birth weights; changes in liver enzymes; and increased cancer risk (“Potential health effects of Pfas Chemicals,” 2022). Because of the level of PFAS and other chemicals present in cosmetics and beauty products, consumers of these products are at a higher, physical risk of their deleterious effects.

Aside from causing physical harm to feminine people, the pressure of avoiding these ailments while still adhering to feminine standards also poses mental risks. In a 2020 article in Harvard Women’s Health Watch titled “Toxic Beauty”, the author outlines ways in which women can limit their exposure to harmful cosmetic chemicals, namely through doing their own research and finding safer alternatives. Such a suggestion falls in line with inducing stress via risk society; more often than not, these safer choices are not obvious. Although the internet makes access to this information more accessible, the history of chemical coverups by the aforementioned companies (Dupont and 3M, among others) have squandered public access and policy making that would completely disclose the presence of these chemicals. The lack of regulation over labeling PFAS prevents consumers from having control over what goes on and into their bodies, leading to stress and anxiety under risk society theory (Gould et al., 2021a).

Responses

Despite the unfolding of harm surrounding PFAS, agencies in the United States are unprepared to regulate labeling or use of these substances in many products, let alone cosmetics. Operating under a “proof of harm” model, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the government agency that oversees the “safety” of cosmetics, requires that their oversights be proven dangerous to require intervention, rather than proven safe before their release to the market. Under such a system, chemical companies with the interest of profiting can get away with poisoning the public and invest in keeping the harm of their products close to their vests without fear of being flagged by the FDA. As of 2023, some states have implemented laws banning certain PFAS in certain capacities (Bright, 2023), even specifically targeting cosmetics (Rathke, 2023). None of these regulations, however, are completely comprehensive in regulating all PFAS in all products.

From a consumer perspective, apps like Yuka, a French, non-brand influenced company, and Detox Me, created by the Silent Spring Institute, offer shoppers the ability to scan products and be instantly notified of harmful chemicals in food or cosmetics. By removing the need for consumers to do their own research, these applications reduce stress in consumers looking to protect themselves from harmful ingredients, but it does place public health in the hands of those curating the scan results. Anti-chemical advocates have also been calling for women to embrace natural beauty and reduce consumption of these products to avoid the chemicals altogether (“Toxic Beauty,” 2020). Apps and reducing cosmetic consumption offer solutions for risk society induced stress among women looking to mediate their PFAS exposure, but they are still a market based solution that doesn’t ultimately encourage reformation of chemical regulation or hold corporations accountable.

Conclusion

Applying a gendered analysis is necessary when reviewing the impact of chemicals on consumers. Men and women have traditionally occupied different spaces within the market, and this has had enduring consequences on the mental and physical health of women, or any person seeking a feminine appearance that is achieved through postfeminism means. The social history of feminine culture and expectations has persisted today into a beauty standard that is not only toxic in the social sense, but also in a physically harmful sense. As such, PFAS, a forever chemical with an increasing list of harms, disproportionately impacts women. This being said, women are not the only class of humanity associated with cosmetic use. Further studies could include applying this research to adjacent identities traditionally linked with makeup (perhaps not coincidentally also oppressed by the patriarchal society), such as the drag, gay men, and trans women communities.

References

Bright, Z. (2023, January 4). Pfas bans, restrictions go into effect in states in 2023. Bloomberg Law. https://news.bloomberglaw.com/environment-and-energy/pfas-bans-

restrictions-go-into-effect-in-states-as-year-begins

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022, November 1). Potential health effects of Pfas Chemicals. The Agency of Toxic Substances and Disease Registry. https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/pfas/health-effects/index.html

Chae, J. (2021). YouTube makeup tutorials reinforce postfeminist beliefs through social comparison. Media Psychology, 24(2), 167–189. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2019.1679187

Daly, M. (2021, June 23). Half of US cosmetics contain toxic chemicals. Miami Times. http://libproxy.unl.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/newspapers/half-us-cosmetics-contain-toxic-chemicals/docview/2581545970/se-2

De Grazia, V., & Furlough, E. (1996). The Sex of Things : Gender and Consumption in Historical Perspective. University of California Press.

Gould, K. A., Lewis, T. L., & Meyers, J. (2021a). Theories in Environmental Sociology. In Twenty lessons in environmental sociology (3rd ed., pp. 197–212). essay, Langara College.

Gould, K. A., Lewis, T. L., & MacKendrick, N. (2021b). Sociology of Environmental Health. In Twenty lessons in environmental sociology (3rd ed., pp. 197–212). essay, Langara College.

Rathke, L. (2023, April 7). States consider banning cosmetics containing pfas. Time. Retrieved April 26, 2023, from https://time.com/6269617/cosmetics-pfas-ban/

Simon, S. (2019, December 6). Study finds possible link between hair dye, straighteners, and breast cancer. American Cancer Society. https://www.cancer.org/latest-news/study-finds-

possible-link-between-hair-dye-straighteners-and-breast-cancer.html#:~:text=A%20study%20from%20researchers%20at,the%20International%20Journal%20of%20Cancer.

Toxic beauty. (2020). Harvard Women’s Health Watch. 27(8), 4–5.Whitehead, H. D., Venier, M., Wu, Y., Eastman, E., Urbanik, S., Diamond, M. L., Shalin, A., Schwartz-Narbonne, H., Bruton, T. A., Blum, A., Wang, Z., Green, M., Tighe, M., Wilkinson, J. T., McGuinness, S., & Peaslee, G. F. (2021). Fluorinated compounds in North American cosmetics. Environmental Science & Technology Letters, 8(7), 538–544. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.estlett.1c00240